Seite 58 im Original

Bazon Brock on Stephanie Senge

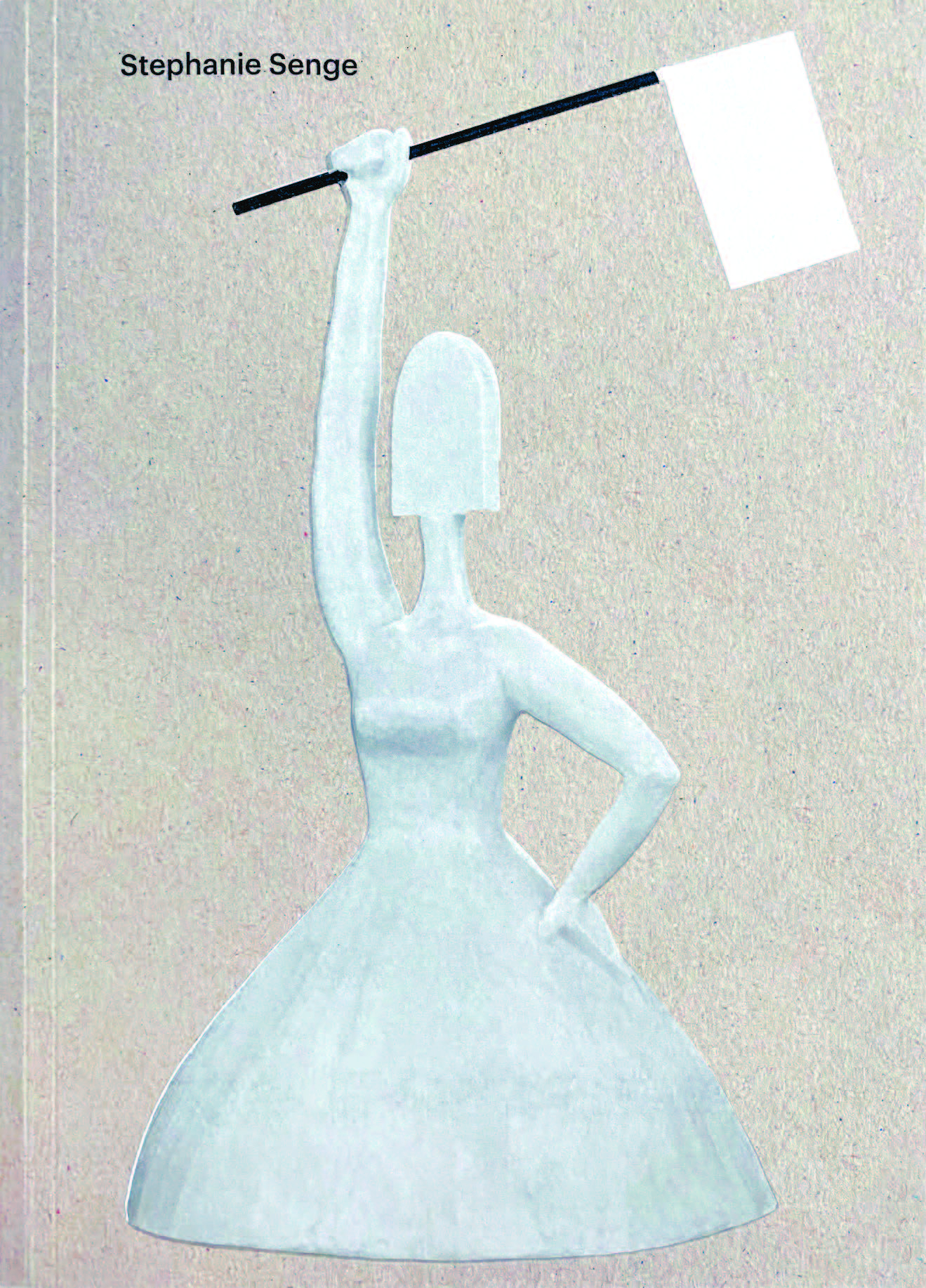

The Library of Consumer Products

For years I have been interested in the work of Stephanie Senge and have been following it very closely because it pertains to my own work, the mediation of aesthetics in everyday life. After all, it is no use playing around artistically in one's studio if it does not provide insight into the world and our everyday lives. So what matters is what artists and scientists find out within their studios – the things they can convey as insights and develop as image processes that are also of use to the user, so really usable – to use. And this means transferring the aesthetics, thoughts on artistic-scientific conceptual work, and the creation or development of images into daily life. That is where Stephanie Senge's idea of relating her aesthetic or artistic sculptural and painterly themes to the most significant sphere of our everyday lives, namely to consumer goods and especially to the distribution of these goods, i.e. department stores/supermarkets, has been quite fundamental. No one had ever done this before.

We had the idea then of expanding on this incredible achievement, which she had long been doing on her own, way before Wolfgang Ullrich and I worked with her on central aspects of our cultural mediation, such as libraries. Today people go to large department stores to get informed about everyday life by seeing what they can purchase for themselves on their respective budgets in terms of cleaning, nutritional, house-hold, and health products just as just as they once did so by going to libraries. We go to supermarkets today, just as we did to libraries, to look at, sort through and judge the range of goods on the shelves. The similarity in layout is quite striking but so is the functional, structural analogy between the displays developed in the context of an old library, namely, rows of books arranged by author and subject area and merchandise displays today, which are also arranged by author – in this case, brands – or categories of goods, special offers, or product groups.

Stephanie Senge has done something quite marvelous here, namely she has transferred the main criteria in the differentiating search strategies that libraries developed to consumer goods, and not wantonly, but by looking at the goods themselves. There has long been found on packaging what we know as cataloging terms used in libraries: beauty, masculinity, health, friendship, love, war and so on. Senge's work shows how these criteria for distinguishing subject areas, according to how books are arranged and offered to the public in libraries, now relates to what can be found on product packaging. This means that in a library we might find 250 pages on a subject such as "Love in Summer Gardens," and perhaps from ten authors; on a product page with 150 sellers, we will see a total of maybe ten lines on the products themselves. And the question we have to ask is how the information contained in these ten lines on the products stands in relation to a variant, let's say, of 150 different products such as laundry detergent on the one hand with the endless amount of information in libraries on the other.

How can we explain this? What does the general public really get out of reading great authors? Who still reads Kant these days? You read Kant in order to say in the end: Kant, that is the philosopher who proved that what people have always said to be true, namely: Do to no one what you yourself dislike. And the summa of all the heavy reading of Kant can actually be summed up in that one sentence. Or another example: Musil, who wrote "The Man Without Qualities." All these authors, Thomas Mann and Gottfried Benn and Goethe and Schiller and the devil only knows, are reduced and compressed by their readers into standardized prestige clusters, sort of cognitive aphorisms. And then we talk about Musil only in terms of what is still remaining in our heads from the beautiful phrase "Man without Qualities."

Even in more classical educational institutions, users reduce hundreds of pages of books down to a few key sentences, to catch phrases, even to children's phrases, to whatever is just appealing enough to spread and promote it further. And it has turned out that using libraries to condense the greatest authors into a few sentences is about the same as what the producers of the goods in supermarkets do with their consumption products and labels. And so, it simply turns out that, for example, the categories "soul", "man," "dreams," "beauty," "time," and "strength" found on the products on supermarket shelves are just as meaningful as what a publisher's announcement says about an upcoming book release. It will be no longer than a line and a half, either. And this analogy is a tremendous insight, in which Stephanie Senge picks up roughly where Walter Benjamin left off in the 1920s, that is, in the mediation of high-culture with subculture, with the overlapping of both these spheres.

In pop culture, this was realized in the 1960s/1970s with the blending of "high and low," in other words, superimposing "high culture" and "low culture," that is, pop being "low culture" on the one hand and the great philharmonic concert works and music history as "high culture" on the other. This overlapping, as Benjamin or authors like Kirk Varnedoe – for example in the large New York exhibition "High and Low" – have done with pop and classical music, has been done by Senge just as stringently and as memorably as Benjamin and Varnedoe, or in current cultural-critical essays that can be read now and then in the critical literature on our times. I think it is brilliant work that an artist is working using the same evidence, that is, with really eye-opening, obviousness in the reasoning put forward such as thinkers like Benjamin or cultural scholars and art historians like Aby Warburg or Varnedoe did. This is a very significant and unexpected accomplishment.

The second aspect of my interest in Stephanie Senge's work, which also prompted me to collaborate with her, was that Wolfgang Ullrich, Stephanie Senge and I founded the society "Ascetics of Luxury – Convent of the Golden Chopsticks" in Munich in 2007, likewise with an interest in exploring and tapping into everyday phenomena – aesthetics in our daily lives has been my topic of interest since around 1965 – in such a way that you cannot avoid the long detour in educational traditions, but you can make it more meaningful.

You can learn more purposefully, you can argue more purposefully and that is contrary to what pop culture, subculture, or "low culture" says; the power of disposal over things has not increased as prices have lowered. If you are buying in a low-price goods segment, you have to throw out all that stuff every three years, every five years. But this makes no economic sense whatsoever. Especially among young people who want to live ecologically sustainably and sensibly, consuming cheap things is the opposite of their actual intentions. Expensive is only sustainable, where there is a real equivalent between quality and price. Expensive and valuable are only what is truly inexpensive. We did not set out to establish a set of rules that everyone has to follow, but rather to instill a general strategy of appreciation and therefore show a sign of respect to the people whose skills produce these kinds of things. We want to encourage the development of distinguishing qualifying criteria that will first establish meaning. This is because there is only one criterion for people on earth to bring meaningfulness into the world, and that is to differentiate between things. Those who cannot differentiate cannot experience anything meaningful in our world. You have to learn to differentiate, and differentiation according to qualities at various levels is the most important criterion.

It was the intention of the society "Ascetics of Luxury" to show that we need to be trained in ecological terms, in economic terms, in cultural hygiene terms, and in communicative terms to focus on what is valuable and to reintroduce a standard of high-quality, because it is only this what is truly sustainable. So, the greatest meaning we can give to the world is an appreciation for what is important, what is valuable, what is significant, but not because it is normatively set in stone somewhere – like when we say Goethe is compulsory at school – but because it corresponds to our own ability to recognize insights, realizations, policy formulation, expansion of consciousness, and power of imagination as being productive for ourselves.